Self-assembling solid-state battery materials

Researchers in the US have developed a self-assembling battery material that quickly breaks apart when submerged in a simple organic liquid, writes Nick Flaherty.

The material can work as the electrolyte in a functioning, solid-state battery cell and then revert back to its original molecular components in minutes. This offers an alternative to shredding the battery into a mixed, hard-to-recycle mass. Instead, because the electrolyte serves as the battery’s connecting layer, when the new material returns to its original molecular form, the entire battery disassembles to accelerate the recycling process.

“So far, in the battery industry, we’ve focused on high-performing materials and designs, and only later tried to figure out how to recycle batteries made with complex structures and hard-to-recycle materials,” says researcher Yukio Cho at MIT. “Our approach is to start with easily recyclable materials and figure out how to make them battery-compatible. Designing batteries for recyclability from the beginning is a new approach.”

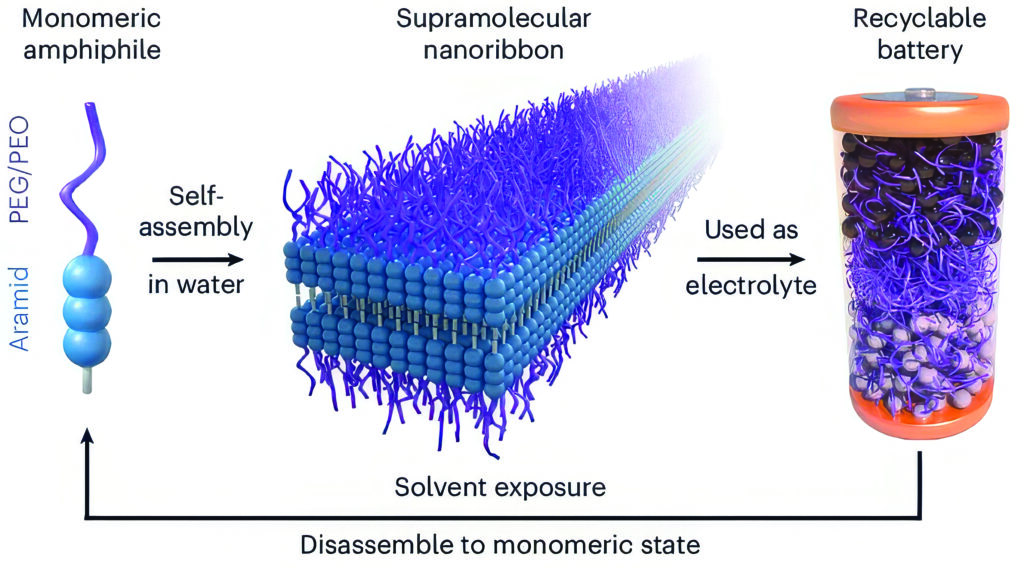

The team used aramid amphiphiles (AAs), the chemical structures and stability of which mimic those of Kevlar. The researchers further designed the AAs to contain polyethylene glycol (PEG) – which can conduct lithium ions – on one end of each molecule. When the molecules are exposed to water, they spontaneously form nanoribbons with ion-conducting PEG surfaces and bases that imitate the robustness of Kevlar through tight hydrogen bonding. The result is a mechanically stable nanoribbon structure that conducts ions across its surface.

“The material is composed of two parts,” says Cho. “The first part is this flexible chain that gives us a nest, or host, for lithium ions to jump around. The second part is this strong organic material component that is used in Kevlar, which is a bulletproof material. Those make the whole structure stable.”

When added to water, the nanoribbons self-assemble to form millions of nanoribbons that can be hot-pressed into a solid-state material.

“Within five minutes of being added to water, the solution becomes gel-like, indicating there are so many nanofibres formed in the liquid that they start to entangle each other,” says Cho. “What’s exciting is we can make this material at scale because of the self-assembly behaviour.”

The team constructed a solid-state battery cell that used lithium iron phosphate for the cathode and lithium titanium oxide as the anode. However, a side-effect known as polarisation limited the movement of the lithium ions into the battery’s electrodes during fast charging and discharging.

“The lithium ions moved along the nanofibre all right, but getting the lithium ions from the nanofibres to the metal oxide seems to be the most sluggish point of the process,” Cho says.

When they immersed the battery cell into organic solvents, the material immediately dissolved, with each part of the battery falling away for easier recycling.

“The electrolyte holds the two battery electrodes together and provides the lithium-ion pathways,” Cho says. “So, when you want to recycle the battery, the entire electrolyte layer can fall off naturally and you can recycle the electrodes separately.”

The material exhibits total conductivity of 1.6 x 10−4 S/cm at 50 C, a Young’s modulus of 70 MPa and toughness of 1 MJ/m3, and serves as a proof-of-concept that demonstrates the recycle-first approach says Cho.

“Our battery performance was not fantastic, but what we’re picturing is using this material as one layer in the battery electrolyte. It doesn’t have to be the entire electrolyte to kick off the recycling process,” he says.

Click here to read the latest issue of E-Mobility Engineering.

ONLINE PARTNERS