Battery electrode binders

(Image courtesy of Andra Febrian)

Bonding power

Binders in EV batteries do far more than simply act as a glue holding the electrodes together, as revealed by Peter Donaldson

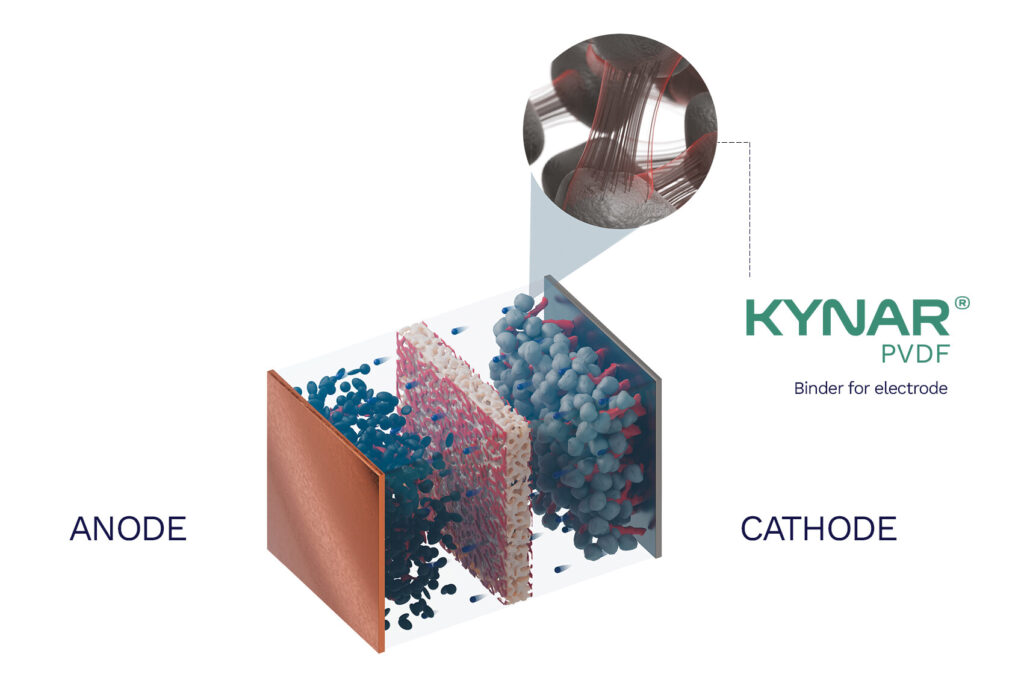

Efforts to improve crucial metrics such as energy density and cycle life in lithium-ion batteries often focus on anode and cathode chemistry at cell level or on pack architecture at the system level – for very good reason because r&d along these avenues continues to yield good results. As in any complex system, however, there are areas that don’t receive as much attention as they deserve, and the ‘glues’ that hold the active particles together in both electrodes, also known as binders, fall into that category. Far more than a glue, a binder is a polymer system that impacts the manufacturing process, the performance and longevity of the cell and, by extension, the battery system and even the vehicle as a whole. The glue function, however, is central because without it, the electrodes would literally crumble.

Providing mechanical cohesion and adhesion – holding electrode active materials together – through many thousands of charge–discharge cycles in which significant and sometimes enormous volume changes take place is a demanding task. Throughout the cell’s life, the binder additionally has the job of maintaining stable electrical and ionic connections within the electrode, ensuring that all particles of the active material remain in contact with each other and with the current collector. This prevents the formation of isolated ‘islands’ of material that cannot take part in the chemical reaction and reduce the cell’s capacity as a consequence. Preventing cracking and other forms of electrode degradation is a closely related function crucial to achieving the battery’s desired cycle life. The binder can also affect the electrode’s thermal stability and its resistance to short-circuiting.

Furthermore, the binder can influence the formation and long-term robustness of the solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer, which is a key factor in cycle life and coulombic efficiency, making engineering of the binder with the SEI in mind a key consideration. Binder performance in all aspects can also be highly dependent on the particle morphology and surface chemistry of the active materials.

(Image courtesy of Arkema)

PVDF dominance challenged

Today, the dominant binder materials that are familiar to the industry, and which have supported the improvement of battery chemistries for years, are based on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). A close look at this semi-crystalline thermoplastic fluoropolymer reveals its pros and cons and sheds light on the key attributes desirable in the current generation of binders, as well as the gaps to be filled by the next. Lithium batteries represent a demanding application for polymeric materials because they require long-term reliability and high chemical and electrochemical resistance within the specific environment of lithium cells. In automotive applications, performance at elevated temperatures is also required. A binder should possess high chemical and electrochemical stability in the reaction environment. In this way, electrical and ionic conductivity are maintained through close contact between particles and good homogeneity.

PVDF’s electrochemical stability – thanks in significant measure to the stability of fluorinated polymers – is one of the reasons it became the industry standard. It is safe to use in cells of up to around 4.5 V (compared with a standard Li/Li+ reference electrode), meaning that it does not undergo oxidation (loss of electrons) or reduction (gain of electrons) within the voltage window of common cathode materials. For a cathode binder, the primary threat is oxidation at high voltage because the cathode operates at a high potential during charging. It also resists oxidation and degradation from exposure to the electrolyte.

Secondly, its good adhesion stems from its formation of strong van der Waals and dipole–dipole interactions with active materials and the aluminium current collector. The van der Waals force is a distance-dependent attraction between atoms or molecules that is not based on chemical bonds but on forces that occur between neutral atoms and molecules due to temporary fluctuations in electron density, leading to induced dipoles. Attraction between the positive end of one dipole and the negative end of another also contributes to PVDF binders’ good adhesion, minimising the risk of electrode delamination.

PVDF also dissolves easily in organic solvents, the type used most commonly being N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), which allows uniform dispersion of active materials and conductive additives, and consistent coating of slurry on polymer or foil backing materials. This uniformity is critical for achieving high electrode density, optimal electronic conductivity and efficient ion transport within the electrode matrix.

It also has a high melting point and good thermal resistance, representing an additional safety benefit. Moreover, its good wettability means that it absorbs liquid electrolyte well, which helps ion transport; its amorphous region is a good matrix for polar molecules, meaning that lithium ions can pass through the layer of swollen PVDF. Its inherent hydrophobicity also helps prevent moisture uptake.

However, the NMP solvent is a toxic volatile organic compound (VOC), which the industry is under pressure to move away from. It is also tightly regulated and requires closed-loop recovery systems that add cost and complexity.

PVDF is also electrically and ionically insulating, which necessitates the use of conductive additives such as carbon black to establish percolation networks that support electrical conductivity. The liquid electrolyte in the electrode’s pores supports ionic conductivity.

While PVDF is generally a strong binder, it has difficulty with materials that exhibit high expansion, such as silicon anodes that expand by around 300% when they take up lithium ions during charging. Obviously, this is not a problem for PVDF as a cathode binder.

PVDF also comes with additional costs from the fluorine-based chemical supply chain that, together with the energy- and capital-intensive nature of NMP processing, provide economic incentives to move to alternatives such as aqueous binders, which use water as the solvent.

Today, PVDF remains the industry standard for cathodes, although research and development continue, focusing on tailor-made solutions to enhance binder performance without compromising safety. Several grades with different molecular weights are available to combine adhesion properties and advantages in electrode manufacturing. Enhanced intermolecular interactions between the polymer, active material and metal collector result in improved performance in terms of adhesion and chemical resistance. These effects translate into higher energy density because the binder content can be significantly reduced, while lower internal resistance allows for increased power density.

(Image courtesy BASF)

Fomenting aqueous revolution

Driven by the perennial need for cost reduction and reduced environmental impact, a shift to aqueous binders is in prospect. Aqueous binders are already used for graphite anodes (very common in lithium-ion batteries), the standard being the combination of styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). While SBR/CMC has high binding strength, it is also sensitive to moisture, which therefore has to be meticulously controlled during manufacture. Additionally, its temperature stability is limited, making it less than ideal for very high-power or high-temperature applications, while its elasticity is inadequate for silicon anodes.

For cathode use, however, the persistent challenge of aluminium current collector corrosion during processing and long-term cycling, especially with high-voltage NMC chemistries, still stands in the way of aqueous binders in mass-produced lithium-ion batteries. Different methods have been proposed to address this, including: control of the slurry chemistry to ensure a buffer pH of around 7–8 and/or using acid (HF) scavengers; and engineering the Al surface using a primer or inorganic passivation on the foil.

Promising new aqueous binders for cathodes are based predominantly on polyacrylic acid (PAA) chemistry, with materials like CMC also seeing some use. The PAA-based LA133, for example, is designed as a drop-in replacement for PVDF that eliminates the toxic NMP solvent, and provides good adhesion and stability for cathode materials such as NMC and LFP. However, while PVDF is inexpensive, PAA is priced at $20,000 to $28,000 per ton, making it a speciality material.

LA133 is a trademarked product, so its exact formulation is secret. However, it is widely acknowledged to be a water-based PAA derivative or copolymer with an acrylic-based backbone and carboxylate salt (-COO⁻Li+) functional groups. These are formed when carboxyl (-COOH) groups lose the hydrogen (a single proton) when reacted with a hydroxide ion (OH-) to yield a carboxylate salt (-COO⁻) and water (H₂O) – the hydroxide ion in question would be lithium hydroxide (LiOH) to yield -COO⁻Li+. This deprotonation/neutralisation is a key design feature that prevents corrosion of the aluminium current collector, provides optimal slurry rheology, and – combined with a stabilised polymer backbone – ensures high-voltage electrochemical stability.

The ratio of -COOH to -COO⁻ in a binder (its degree of neutralisation) is a critical, tunable parameter for battery engineers, and is a key differentiator between PAA-derived binders suited to silicon anodes on the one hand and cathodes (as above) on the other. For silicon anodes, a high -COOH content is essential to enable strong hydrogen bonding with the silicon oxide layer for realisation of the elastic adhesion essential to accommodate silicon’s massive expansion caused by its absorption of lithium ions, while aqueous cathodes require a high -COO⁻Li⁺ content for Al corrosion protection and slurry stability.

For silicon-dominated anodes, the primary goal for next-gen binders is maximising the elasticity to accommodate silicon’s large volume changes, measured by capacity retention over 500 or more cycles and coulombic efficiency greater than 99.5%.

However, advanced binders in general and aqueous ones in particular affect slurry rheology (shear-thinning) and drying behaviour, requiring tighter process controls (pH, viscosity and drying ramps) to avoid defects like cracking. Furthermore, switching from PVDF/NMP to aqueous systems can reduce OPEX and CAPEX (no NMP recovery is needed, for example) but may introduce higher quality risks and lower yields.

(Image courtesy of BASF)

Conductive binders

Both energy- and power-density in lithium-ion cells can be improved by reducing the resistance to electron and ion flow in anodes and cathodes, much of the electronic portion of which is caused by the inherently insulating nature of polymers such as PVDF. This is where conductive binders come in. These can replace carbon black to improve energy density but are 20–40% more expensive than traditional systems (SBR/CMC + CB). Key challenges include poor mechanical properties and electrochemical degradation.

The most prominent conductive binders are those based on the polymer complex known as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (PEDOT)) and polystyrene sulphonate (PSS) – collectively referred to as PDOT:PSS. The charge-carrying PDOT component is a conjugated polymer that is intrinsically conductive in its doped state. The PSS component is a water-soluble insulating polymer with two roles. In its first role, the sulphonate groups dope the PDOT chain, making it conductive, while its second role is to act as a dispersant so that the otherwise insoluble PDOT can form a stable water-based dispersion or ‘ink’.

However, PDOT:PSS comes with a number of limitations that the industry is working to overcome. While this binder is electrically conductive, it is a poor conductor of ions, meaning that lithium-ion transport can be hindered, particularly in thick electrodes, limiting charge/discharge rates. The thiophene-based backbone of the PDOT component can be electrochemically unstable at cell potentials above 3.8 V. It can undergo oxidation and degrade cathode surfaces, causing capacity to grow and impedance to fade, severely limiting its use with high-voltage cathode materials such as NMC and NCA. Also, the PSS component is highly acidic and corrosive to the cathode’s aluminium current collector foil and it can also degrade active materials, necessitating the use of costly neutralisation or barrier layers. The film is also hygroscopic, and retention of water is catastrophic for cell assembly and long-term performance, so extremely thorough drying is demanded. Furthermore, its adhesion to electrode materials is often inferior to that of binders such as PAA and PVDF. Hybrid systems in which PEDOT:PSS is mixed with a stronger binder are being explored but dilute its conductivity. Lastly, its cost is orders of magnitude higher than that of traditional binders and carbon black.

Research and development to mitigate these problems focuses on niche applications and material modifications. The most promising application for PEDOT:PSS is in silicon or silicon-based anodes because it can accommodate silicon’s expansion while providing both binding and electronic conductivity, and its poor voltage stability is not a problem in the anode where voltages are typically between 0.1 and 0.8 V.

One area of focus for material modification is treating PEDOT:PSS with solvents such as dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) or ethylene glycol, for example, or with bases to increase its electronic conductivity and reduce acidity. Another is on hybrid/composite binders in which PEDOT:PSS is used with small amounts of a strong adhesive binder such as PAA, or incorporating inorganic nanoparticles to improve adhesion and stability.

As with other conductive binders such as π-conjugated polymers, or hybrid ionic–electronic conductors, PEDOT:PSS can eliminate or drastically reduce the need for carbon black, thereby improving volumetric and gravimetric energy density. However, their cost is higher owing to the more complex synthesis process, leading to higher battery cost-per-cycle-life, making them about 20–40% more expensive than SBR/CMC + CB electrodes.

(Image courtesy of BASF)

Conductive competitors

Overall, PEDOT:PSS is transformative in concept, but remains challenging for mainstream EV batteries – because of its high cost in particular – and there is significant r&d into potential competitors. For anode applications, these include intrinsically conductive polymers (ICPs), carbon-based conductive binders and multifunctional hybrid/composite binders.

ICPs such as polyaniline (PANI) and polypyrrole (PPy) compete directly with PEDOT:PSS but come with their own trade-offs. PANI offers good conductivity, but its complex doping/de-doping chemistry in the battery voltage window can be unstable and lead to side reactions. PANI is often used in composite binders. PPy polymerises relatively easily but, like PEDOT, has marginal stability during long-term cycling. Furthermore, most ICPs suffer from poor ionic conductivity and can swell/shrink with their own redox reactions, compromising their stability as binders.

As a group, carbon-based conductive binders constitute important pragmatic competition for PEDOT:PSS. The most promising examples include graphene oxide (GO) / reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and carbon nanotube (CNT) ‘liquids’ or dispersions.

To make a GO/rGO binder, GO is dispersed in water and coated onto the active anode particles, then chemically or thermally reduced to rGO, which wraps the particles in a web that provides excellent conductivity and mechanical strength along with the flexibility to accommodate silicon’s expansion. The downside of GO/rGO is a combination of high cost and complex processing, plus a high specific surface area that can lead to excessive SEI formation and consequent low first-cycle efficiency.

When functionalised for dispersion, CNTs form a percolating conductive and adhesive network. Their main advantage is extremely high conductivity at low loadings, but they are expensive, dispersion stability is marginal and they are potentially toxic.

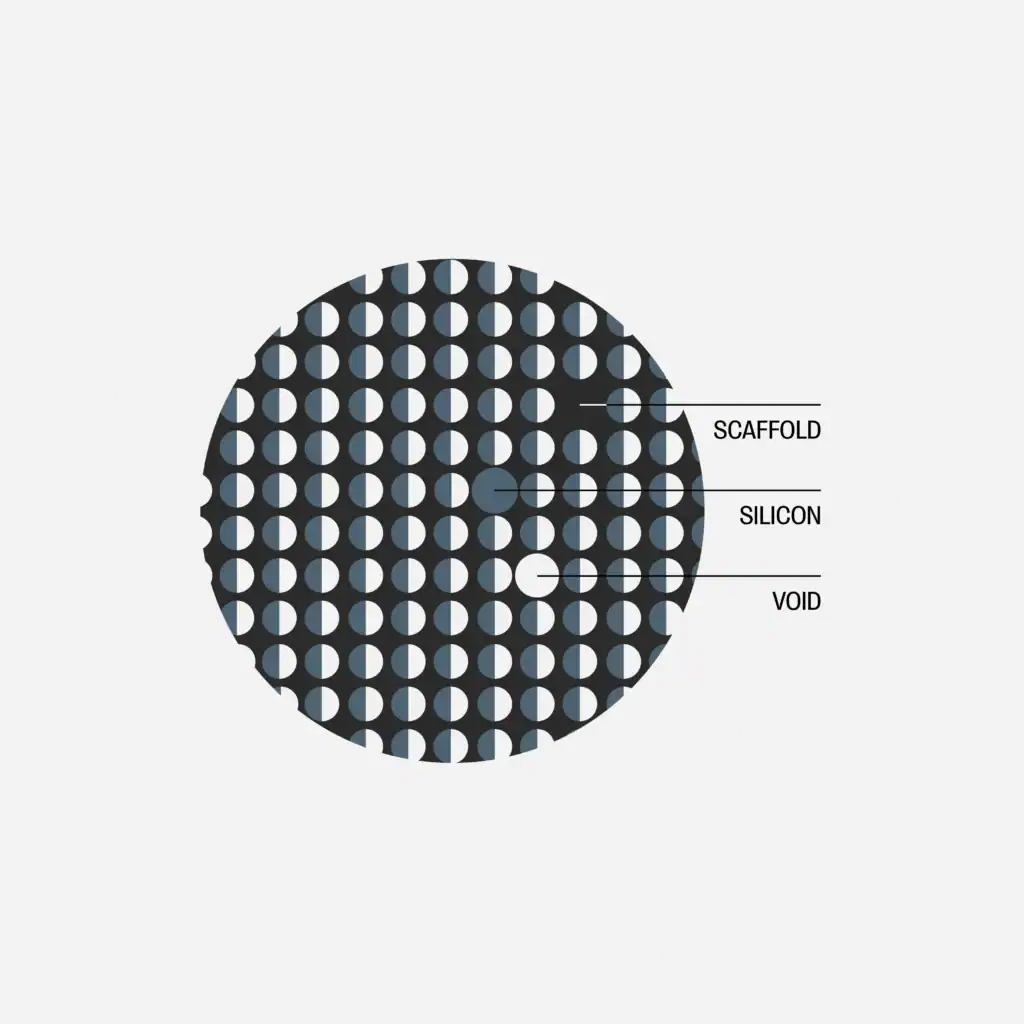

Silicon–carbon anode

At this point, examination of a leading developer’s highly innovative silicon–carbon composite anode material, and the selection of a suitable binder, is enlightening. Here, nanoscale amorphous silicon is grown inside a porous carbon matrix via (silane) gas-phase infiltration to produce a material that combines the high capacity of silicon with the conductivity and structural stability of carbon. The particle architecture is roughly 1/3 silicon, 1/3 carbon, 1/3 void by volume. The internal void space is critical because it accommodates silicon’s expansion internally, preventing particle fracture and excessive electrode-level swelling. This makes it a more forgiving ‘drop-in’ material for existing battery manufacturing lines. It is also designed for flexibility, usable in blends with graphite (e.g., 5–10% replacement) or as a 100% silicon–carbon anode.

While the roles played by the binder in this composite anode material are common to all binders for silicon anodes, the developer stresses that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, and that the optimal binder depends on the specific battery application and how it ranks high-power, long-life automotive, and cold-weather operation, for example. The company also emphasises that the binder formulation must suit the proportion of silicon in the anode. Graphite-dominated low-silicon blends can use more traditional binders such as SBR/SMC, while high-silicon (even 100%) anodes require specialised binders such as polyimide-based materials with higher mechanical strength and thermal stability.

Also, close collaboration between the anode developer and the binder supplier is crucial to understanding how binder chemistry interacts with the silicon–carbon surface to ensure commercial success. The company’s particular silicon–carbon composite anode works with SBR/CMC, PAA, PEI, and other specialty binders, but the selection is purpose-driven.

(Image courtesy of Group14)

Cathode hurdles

Cathodes present conductive binders with a much harsher environment than do anodes because the higher potentials encountered (4.3 V and above) cause high-voltage oxidative stress, so stability under these conditions is essential. The main categories of materials under investigation for cathode use are: oxidatively stable conductive polymers (OCPs), conjugated coordination polymers / metal–organic frameworks (CCP/MOFs), ion–electron mixed conductors (IEMCs) and cathode binders with ‘electronic wiring’.

The first example of an OCP binder material is poly (9,9-dioctylfluorene-co-fluorenone-co-methylbenzoic ester). Thankfully abbreviated to PFM, this is a fluorene-based polymer designed specifically for cathode use. Its conjugated backbone is engineered to withstand high oxidation potentials of 4.5 V and above. PFM significantly boosts the rate capability of LFP and NMC cathodes in research. Additionally, polymers with rigid, ladder-like backbones, such as polybenzimidazoles, are exceptionally stable both thermally and electrochemically, but conductivity is often lower and processing is difficult.

The second category – the CCP/MOF materials – have intrinsic porosity to ease ion transport and, if designed with conjugated linkers, can maintain useful electronic conductivity. Now in the early stages of r&d, much work has to be done to solve cost and complexity challenges, and to ensure stability in the electrolyte environment. Testing for electrolyte capability involves chemical screening, thermal analysis, electrochemical cycling and post-mortem studies to prevent side reactions with new electrolyte chemistries.

(Image courtesy of Mercedes-Benz)

Natural polymers

Another line of binder development focused primarily on sustainably sourced silicon anodes is that of ‘natural’ polymers. Substances such as seaweed-derived alginate and chitosan, derived from crustacean shells, are promising because they are rich in functional groups (carboxyl in alginate, amine in chitosan) that form strong, multivalent hydrogen bonds with silicon particles, effectively accommodating volume expansion and improving cycle life. These are relatively inexpensive, renewable, enable aqueous processing and are easier to recycle.

They present significant barriers to commercial adoption, however, primarily in terms of batch-to-batch variability and purity. Their molecular weight and percentage of impurities such as sodium and calcium ions fluctuate, which is unacceptable for gigafactories’ demand for absolute consistency, while the necessary purification to battery-grade standards is costly, so far, and unscaled. Also, these hygroscopic polymers complicate slurry preparation and drying, possess limited thermal stability compared to synthetics such as PVDF, and are electronically and ionically insulating.

Development is in the advanced r&d stage, focusing on chemical modification, crosslinking and blending with synthetic binders (SBR/CMC for example) to optimise performance and processability. Their most likely path to market is as performance-enhancing additives in hybrid systems or in niche, high-silicon applications where their adhesive superiority justifies the supply chain complexity. Ultimately, their success depends less on electrochemical promise and more on establishing a reliable, high-volume supply chain that can deliver the consistent purity required by automotive-grade battery manufacturing.

Conducting ions and electrons

In cathodes, ionic conductivity is as critical as electronic conductivity, so binders that facilitate both represent the ideal, but this is difficult to achieve. One candidate material is lithiated Nafion. Better known as the membrane material in proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells, its use in battery cell cathodes involves lithiation to enable it to conduct Li+ ions, although its electronic conductivity is low. The second set of candidates in this category consists of designer polymers with built-in ionic functional groups such as lithiated sulfonate (-SO₃Li) or carboxylate (-COOLi) groups tethered to a stable backbone, the idea being to create pathways for Li⁺ motion to move through the binder matrix.

Such designer ionic binders tackle a fundamental transport limitation, but they introduce a new set of electrochemical, mechanical and processing complexities. The core challenge is that ionic conduction in solids is inherently linked to soft, dynamic materials, while strong binders are inherently rigid and static. Breaking this inverse relationship is a fundamental problem in materials science.

For now, the pragmatic approach is to pursue ultra-efficient traditional binders with optimised conductive additives. Using a highly stable, minimally insulating aqueous binder (such as LA133) in combination with optimised, lower-loading conductive additives (such as single-wall CNTs or specialised carbon blends) is a promising development path. The goal here is to lean into the binder’s core function as a stable glue, while integrating a conductive network so efficient that its weight penalty is kept to a minimum.

Solid-state options

As solid-state battery (SSB) technology advances, polymeric binders are expected to play an increasingly critical role. They will evolve into functional components of composite electrolytes, requiring ionic conductivity, elasticity and stability at solid–solid interfaces.

Materials such as high molecular weight polyisobutylene (HM-PIB) are well suited to meeting the evolving demands at the solid–solid interface – there’s no liquid electrolyte in SSBs – and within composite electrodes and electrolytes. HM-PIB provides excellent adhesion, ensuring strong bonding between battery components and enhancing structural integrity. It also has a unique cold flow property that allows it to bridge gaps between particles, promoting efficient ion transport and connectivity within the solid-state matrix. These materials also offer superior elasticity and elongation, enabling them to accommodate electrode expansion and contraction, thereby reducing the risk of physical damage or premature failure.

As HM-PIB materials undergo evaluation for use in next-generation SSBs, the focus will be on optimising properties like flexibility at low temperatures, chemical inertness and the ability to act as a bridge at the solid–solid interface, all of which are essential for this application.

Making binders smart

Smart binders represent the frontier of battery materials science, moving from passive components to dynamic, responsive systems. The most researched type are self-healing binders, designed to repair the microcracks that form in electrodes owing to volume changes (in silicon anodes, for example) autonomously. They achieve this through reversible chemistry, which involves dynamic covalent bonds (such as boronic esters) or supramolecular interactions (such as hydrogen-bond networks) that can break under stress and reform afterwards, effectively ‘healing’ the electrode structure.

A seminal example is a self-healing binder network constructed from PAA dynamically cross-linked via urea-functionalised linkers. The urea groups form dimers through quadruple hydrogen bonds, which provide strong mechanical cohesion but are sufficiently reversible to break and reform under mechanical stress. In laboratory tests with silicon nanoparticle anodes, electrodes employing this binder maintained structural and electrical integrity for hundreds of cycles. In stark contrast, conventional electrodes using a PVDF binder typically fail owing to irreversible cracking within a few tens of cycles.

Other smart concepts include polymers that respond to stimuli, for example changing conductivity or adhesion with temperature or voltage. Thermo-responsive block copolymer binders represent a class of smart materials designed to adapt electrode properties to operating temperature, for example.

These copolymers typically combine a rigid structural block (such as polyimide) with a soft block exhibiting a Lower Critical Solution Temperature (LCST), such as poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). Below the LCST, the PEO blocks are hydrophilic and swell with electrolyte, promoting ionic transport. Upon heating during high-power operation (to 50–70 C, for example), the PEO blocks undergo a sharp phase transition, becoming hydrophobic and collapsing. This collapse induces two critical effects: first, it mechanically contracts the polymer network, pulling active material particles closer together to reduce interparticle electronic resistance; second, it vacates volume previously occupied by swollen polymer chains, generating additional nanoporosity for improved ionic transport – just when needed most. In this way, the binder dynamically reconfigures the electrode’s tortuosity and contact network, optimising it for prevailing conditions – effectively providing intrinsic, material-level thermal management.

Currently, smart binders remain in advanced academic and early-stage r&d, with impressive lab-scale results but unproven scalability. The most significant hurdles in scaling-up include monomer purity, batch consistency and low yields at scale. Although binders are a small part of battery cost (at around 1%), scaling new materials requires proven performance and consistency to justify adoption.

Binder selection can no longer be treated as an afterthought because it is a fundamental design choice that co-optimises cell performance, manufacturability and cost. The evolution of binder technology will continue to be a critical, if unseen, enabler of better EV performance.

Some suppliers of battery binders

Arkema

Ashland

BASF

Daikin Industries

ENEOS Corporation

Kureha Corporation

LG Chem

Resonac

Sumitomo Seika

Synthomer

Syensquo

Targray

Trinseo

Zeon Corporation

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following for their help with this article: Thorsten Schoeppe (Technical Sales) and Dr. Michael Koch (Global Marketing) at BASF; Rick Costantino, founder and CTO of Group14 Technologies; and Anne Risse at Synthomer.

Click here to read the latest issue of E-Mobility Engineering.

ONLINE PARTNERS