Stok Electric

(All images: Stok Electric)

Smooth sailing

Peter Donaldson launches an investigation into the conversion of classic leisure boat Mira to electric power

Given proper care, boats can have very long working lives. At a time of rapid development in powertrain technology, therefore, older workboats, ferries, inspection vessels and leisure craft are potentially great candidates for conversion to electric power. This is the business that the Stokman brothers, Berend and Antonie, got into in 2020 when they formed Stok Electric. Based in the port of Makkum on the Ijsselmeer in the Netherlands, they have broader ambitions for the company and are now also eyeing new build vessels.

“We’ve kept our system as integrated and simple as possible so that the existing fleet can participate in this transition,” co-founder Berend Stokman says. “Many have a lifespan of 100 years if properly maintained, while their diesel engines may only last for 20 years, so this is a great opportunity to replace them.”

However, classic leisure craft are where Stok Electric started, and it recently converted and delivered Mira, a 12 m, steel-hulled motor cruiser built in 1953 by De Vries Lentsch. This yard was a founding member of the consortium of specialised Dutch shipbuilders known as Feadship, which was formed in 1949 and became world famous for construction of custom superyachts.

Classic cruiser

One of a series of 25 constructed for export to the US, Mira is the only one that remained in the Netherlands, and its conversion to electric power was prompted by the diesel engine reaching the end of its service life.

Whether a leisure boat makes a good candidate for conversion depends mainly on its value and its remaining life. “We’d say it’s worthwhile for boats with a lifespan of 20 years or more. For commercial vessels, it’s definitely worthwhile because the investment can be recouped in about three years,” he explains. “Steel or aluminium vessels often have a long lifespan, so those are the types of boats we encounter in refits, while polyester is more suitable for new construction.”

Owners of classic boats choose electric power because they want modern performance without compromising the original aesthetics. “We design our systems to be as compact and integrated as possible, so most of the technology is hidden,” he says.

This can be a major challenge, as the company found out with its first conversion, the subject of which was Elysium, a Truly Classic 56 sailing yacht with the engine room below the galley. With the diesel removed, room in this tight compartment was found for the electric motor and the auxiliary generator. “It’s a beautiful yacht but every space is small, curved and carefully finished, so there was very little room to work.”

He emphasises that the company has learned a lot from the challenging refits with which they started, and that they want to keep doing such one-off projects, although they no longer have to be fully custom installations. The experience helped with the development of a standardised, modular system that makes custom projects easier to execute.

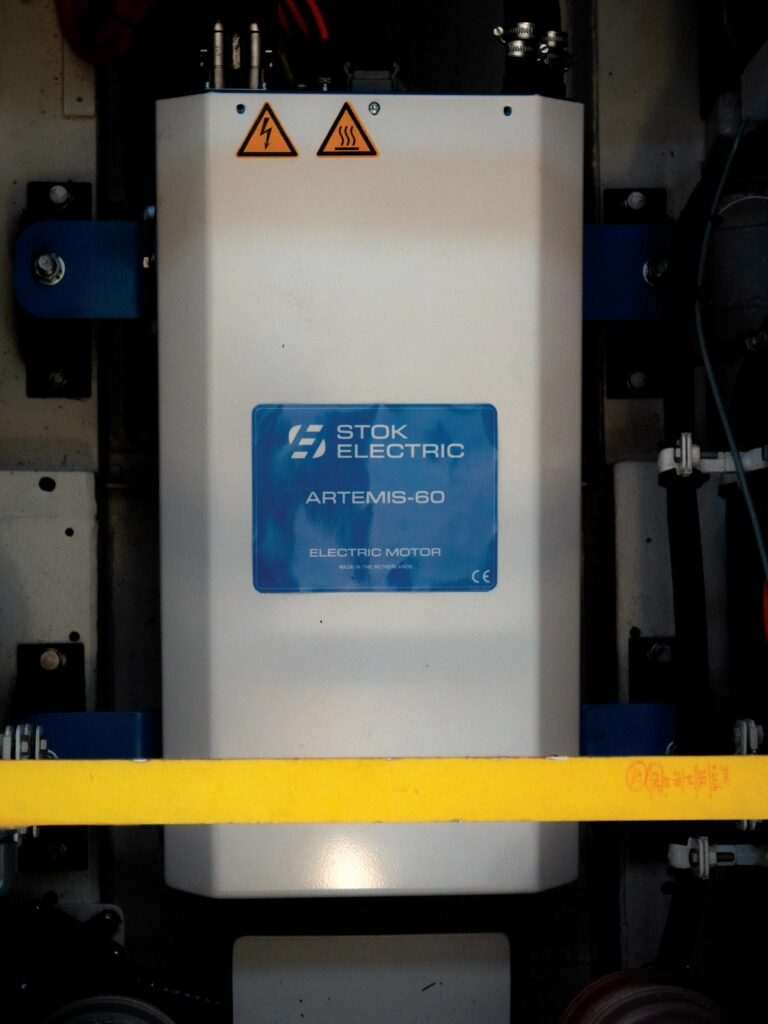

In-house motor

In Mira, Stok Electric installed a liquid-cooled Artemis 60 motor of their own design rated for 60 kW maximum continuous power and 80 kW peak, which is more than adequate for an 8 tonne leisure cruiser with a semi-displacement hull.

Since renamed EPM 60, the motor is a radial-flux AC unit of the permanent magnet synchronous machine (PMSM) variety. It operates at 358 V and produces maximum continuous torque of 384 Nm. Optimised for marine use, it is sealed to the IP65 standard, installed in a direct-drive arrangement and rated for 1500 rpm. The motor also has a degree of redundancy in its control system because it can still operate – albeit somewhat less efficiently – even if a position sensor fails.

Both motor and controller are cooled by a closed-loop water–glycol system that rejects heat to the surrounding water via a hull-mounted heat exchanger. For vessels with aluminium or steel hulls, Stok usually uses either a box cooler, which is a structural component welded to the inside of the hull, or a bun cooler, which is cylindrical unit fitted into a hole cut in the hull plating and mechanically secured and sealed. However, in Mira there was insufficient space for the size of bun cooler required, so Stok uses an internal heat exchanger cooled with pumped-in seawater of the type normally used in polyester-hulled boats.

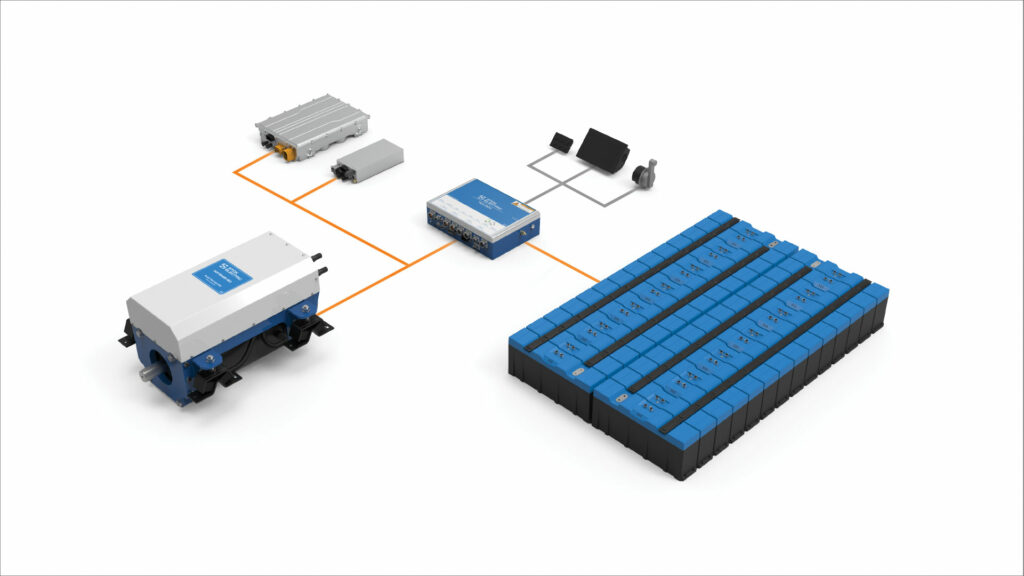

For the power electronics, the company works with established suppliers such as Sevcon and NX, whose technology is used in the automotive industry worldwide. The choice between them depends on required power range. As a rule of thumb, Stokman says, they keep current below 300 A and raise the voltage to increase the power, which keeps the system efficient and reliable.

Based on an insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) inverter, the motor controller is closely integrated with the motor and mounted directly on its frame, minimising wiring and easing installation. The Stok team chose IGBTs for their reliability, robustness and lower electromagnetic emissions than SiC transistors, thanks to their slower switching – which makes filtering simpler – and their tolerance of spikes in voltage and current.

Bidirectional converter

A 2.8 kW bidirectional DC–DC converter links the high-voltage (HV) battery system to the 24 V service battery bank that powers all the onboard systems from navigation equipment, lights and bilge pumps to appliances such as the induction hob and refrigerator. This converter proved relatively difficult to place aboard Mira. “Since then, we’ve integrated the DC–DC directly on the motor frame, so future installations are much simpler and shipyards don’t need to worry about separate mounting.”

In normal use, the converter supplies the service bank from the HV pack, but it can also transfer charge in the other direction. This means that, in principle, the entire system can be fed by a single standard service bank charger from Victron or MasterVolt, for example, eliminating the need for HV charging equipment. However, Mira also has a 22 kW combined charging system fast charger capable of charging the main pack within 3 hours. Both chargers are also bidirectional, potentially enabling the boat to support the local grid in a marina or a home power system.

The bidirectional converter also enables the service bank to act as a backup propulsion battery, providing enough power to manoeuvre the vessel at very low speed. Mira also has a 10 kW AC generator that can charge the main battery pack via the onboard fast charger.

All the HV components are sealed to IP67 or IP6K9K standards (except one motor connector that is IP65 rated) against both water and dust, while all housings are powder-coated aluminium and all busbars are nickel plated. All the HV cables are fitted with sealed connectors and incorporate an HV interlock loop (HVIL) safety system that automatically shuts down the system if a connector is opened or compromised. There is also an isolation monitoring system that constantly measures the resistance of the insulation between the HV system and the hull, which will shut down the system safely if it detects a fault.

User interface

The interface through which the boat’s skipper controls the powerplant and monitors its key parameters is fully integrated with the rest of the marine electronic systems using the CAN-based NMEA 2000 (IEC 61162-3) standard. This allows all key data to be displayed on existing chart plotters. In addition to the screen, there is also a dedicated control panel with push buttons for the most critical functions – such as switching the system and the chargers on or off – that also displays direct status indications and error codes. Additionally, Stok Electric developed its own throttle control built from marine-grade aluminium and incorporating a redundant hall sensor.

The interface shows the battery’s state of health (SoH) and state of charge, the voltage and current draw, charging status, power delivered by the DC–DC converter to onboard consumers, range as a number and a circle on the chart plotter, throttle position and any error codes – accompanied by messages to guide troubleshooting. Under development is a maintenance overview with which the system will indicate when a service is due or components need attention.

No drawings were available, which meant that the engineering team had to work from measurements on the boat itself when designing the installation. One of the key challenges was alignment because the direct-drive motor doesn’t need a gearbox, meaning that the shaft line is higher than that of a diesel engine. Therefore, the motor has to be as compact as possible in both length and diameter to fit low in the hull. Rubber mounts both absorb residual vibration and ensure electrical isolation from the hull.

“The motor we chose was the largest that could be installed in the available space, and it turned out to be the perfect balance. With trim flaps added under the stern, Mira now sails at the same speeds as before, reaching 13 kt.”

Flexible connection

A critical task early in the design of the installation was connecting the motor to the existing propeller shaft. For this, they used a Python Drive flexible coupling that includes a thrust bearing that takes up small misalignments between the motor and the shaft. “It also absorbs vibrations and protects the drivetrain, which is especially useful when replacing a diesel with a direct-drive electric motor,” Stokman notes.

Also crucial to performance and efficiency was matching the propeller and the motor – the behaviour of which is very different from that of the original power unit. A diesel engine delivers its torque in a relatively narrow rpm band, while an electric motor gives maximum torque from zero and then holds a flat torque curve, he explains. The company works with propeller manufacturers to select a propeller or to design one, which was the case with Mira. “The goal is to align the motor’s continuous power output and optimal rpm range with the propeller load curve.”

Several factors influence propeller matching, one of which is hull type because displacement hulls and planing hulls behave very differently. One of the most important factors is the hull resistance curve, which determines how much thrust (and therefore torque) is needed at each point in the boat’s speed range. With a direct-drive application like that adopted for Mira, the propeller’s diameter and pitch are chosen to match the motor’s nominal shaft speed of 1500 rpm. Finally, a balance has to be found between efficiency and manoeuvrability because a prop optimised for cruising might differ from one focused on thrust at low speeds – in harbour manoeuvres, for example.

“By carefully matching motor and propeller, we ensure the system runs efficiently, avoids overload at low speeds and delivers smooth performance that equals or surpasses that of the old diesel installation.”

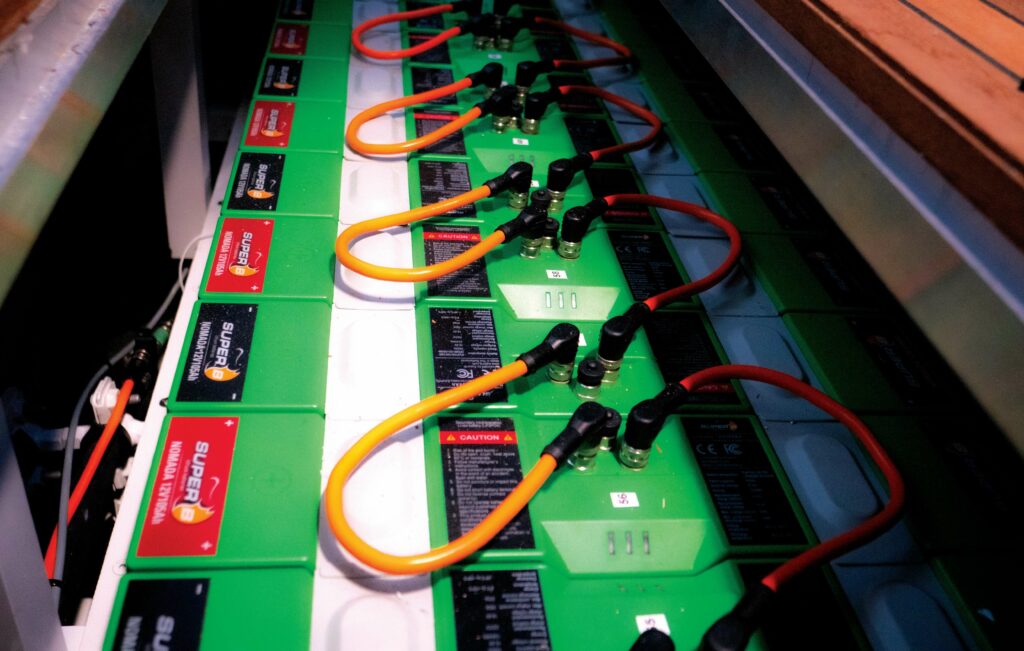

LFP pack and BMS

Batteries are placed as low as possible in the boat, but always in locations where they remain accessible for inspection and maintenance. The battery pack installed in Mira is built up of large prismatic cells of lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4; LFP) chemistry, chosen because they are well proven, widely available and cost-effective. “Safety and long cycle life are the key advantages of LFP chemistry; it’s thermally very stable, reliable and well suited for the marine environment.”

Mira has a 75 kWh pack made up of two strings of 28 x 12.8 V modules from Super B, each connected in series to reach the 358 V required by the motor. “With just one string [around 37.5 kWh], the discharge current would have been too high at full power,” Stokman notes. “That comes down to the C-rating of the battery; it defines how much current a battery can deliver relative to its capacity. If you push too much power from a small pack, the cells run at a high C-rate, which causes extra heat and faster aging.

“To avoid that, we doubled the capacity to 75 kWh. This not only reduced stress on the cells but also matched the owner’s request for at least 100 km range. In practice, Mira now achieves about 130 km at a cruising speed of 6 kt, and 75 kWh was also the maximum we could physically fit on board.”

Stok Electric uses battery management systems (BMSs) from its battery suppliers MG and Super B – the latter in the case of Mira – and fully integrates them into the propulsion system so that all the components communicate with each other. “For example, when the batteries are running low, both the motor and the generator are aware of it. At the same time, every component can also operate independently if communication is lost, which adds an extra layer of reliability.”

The BMS continuously monitors the voltage and temperature of each cell, and calculates the state of health (SoH), shares it with the propulsion system, and then makes the information available through the onboard control and display interface.

Like all the company’s battery packs, the one in Mira is passively cooled. They are designed and sized to avoid generating excessive heat, he explains. “Most of the boats we work on are displacement vessels, which don’t require the very high discharge currents you see in planing hulls. In practice, the heat build-up is limited and, if needed, we add simple ventilation in the battery compartment to keep temperatures stable.”

The HV systems, including the battery packs are built to comply with ES-TRIN for vessels used on inland waterways and DNV rules for larger and more complex projects. To meet ES-TRIN safety requirements, for example, the installation must comply with IEC 62619 for lithium-ion batteries in industrial applications, and IEC 62620 covering performance requirements for large-format cells and modules.

Despite the weight of the large battery pack, the overall displacement of the vessel is essentially unchanged and, while the centre of gravity has shifted slightly aft, Stokman notes that the change is barely noticeable. “What owners do notice is the handling,” he adds. “With instant and smooth torque from the electric motor, manoeuvring becomes much more precise and responsive. So, while trim and balance remain practically unchanged, the driving experience is clearly improved.”

Stokman notes that the battery packs are rated to between 3000 and 6000 cycles, depending on depth of discharge and operating conditions. In automotive applications, LFP batteries have been shown to retain more than 70% capacity after many years of daily use. However, most boats run far fewer cycles than cars and therefore he expects the batteries to last well over a decade in normal use. “Looking ahead, we want to develop a refurbishment and revision program; reusing modules that are still healthy and giving packs a second life.”

The battery pack is connected directly to the power distribution unit (PDU), which the company developed in-house. This subsystem distributes power between the motor, batteries, DC–DC converter and charger, and also houses the main contactors, fuses, isolation monitoring and safety logic.

In most conversions, the installer custom-builds the PDU, which can be a time-consuming and error-prone process. By the time that Stok Electric was working on Mira, however, it had developed the PDU into a standardised plug-and-play unit. “That process took many iterations, but the result is a unit that’s easier to install, safer and far more reliable than any comparable custom solution.”

Testing regime

Before installing the new electric propulsion system, the Stok team connects it all up on a test bench and runs it to make sure that all the hardware, software and communications are working properly. This hardware-in-the-loop validation includes the use of software to inject faults through the CAN bus to trigger loss of BMS comms, loss of throttle and sensor mismatch, for example. Electrical safety checks cover the precharge sequence, detection of contactor welding, over- and under-volt conditions, over-current limits, and derating in response to high/low temperatures. Isolation testing verifies the insulation monitoring thresholds with a calibrated leakage resistor, and ensures that the system detects when the HVIL has opened the HV circuit. The remainder of the fail-safes are also tested to show that the BMS opens the main contactors when it should, that the motor can continue running if position sensing fails, and that the DC–DC converter reverts to a safe state.

Once the system is installed and the boat is in the water, the watertight integrity and ventilation functions of all the housings are checked. Then, the resistance of the insulation between the HV circuit and the hull is tested with a megger before the system is energised. The final test before under load trials commence at sea verify the system’s ability to restart using power from the service pack via the DC–DC converter after the emergency stop has cut the HV power.

Next, the boat is put through a structured in-water testing protocol to validate performance, efficiency and safety. Typically, this is done in two half-day sessions spread over two days, Stokman notes.

The testing protocol starts with checks at the dock to verify all high- and low-voltage connections, isolation monitoring, fuses, the emergency stop function and communication between components. Next comes an initial run at low power to check shaft alignment, vibration levels and steering response. Cruising trials follow in which power draw and speed are measured and efficiency calculated at typical cruising rpm for comparison with the expected range. Then, a full-power trial is conducted, lasting for at least an hour at maximum continuous output to validate the thermal behaviour of the motor, controller and batteries, and the derating and alarm functions. Manoeuvring tests come next, with the boat put through tight turns typical of harbour operations, its ahead–astern response checked and ‘crash’ stops carried out to verify control authority under electrically stressing conditions. Finally, in the safety and redundancy checks, faults are simulated by disconnecting sensors and tripping breakers, for example, to ensure that the system reacts safely and displays error codes correctly.

Next phase

From Mira and other projects, the company learned that hardware has to come first, Stokman reflects. “A marine drivetrain needs to be rock solid and reliable. That’s why we invested so much in motors, PDUs and battery integration.

“The next phase of our r&d is all about software and user experience. We’re developing smarter interfaces, remote monitoring and diagnostics, and remote control functions so that shipyards, fleet managers and owners can get real-time insights into their systems anywhere in the world.”

Click here to read the latest issue of E-Mobility Engineering.

ONLINE PARTNERS