Ryvid

(All images courtesy of Ryvid)

Is this the future of mass mobility?

The ambitious founders of Ryvid have created a range of motorbikes designed to electrify the mass market in the Far East, then take over the streets of every major town and city on the planet, reports Will Gray

Ryvid was founded by three California-based engineers who grew up in Vietnam. Their birthplace has now become one of the most polluted places on Earth, ranked plum last of the 180 countries in last year’s Environmental Performance Index. In early January, it was home to not one but two of the world’s five most polluted cities.

Across Southeast Asia, Vietnam’s greenhouse gas emissions from road transport are second only to those of Indonesia, and they have been increasing by an average of around 15% per year over the past decade. The 74 million motorcycles on the roads of Vietnam represent one of the major contributors to this increase – and that is exactly why Ryvid exists.

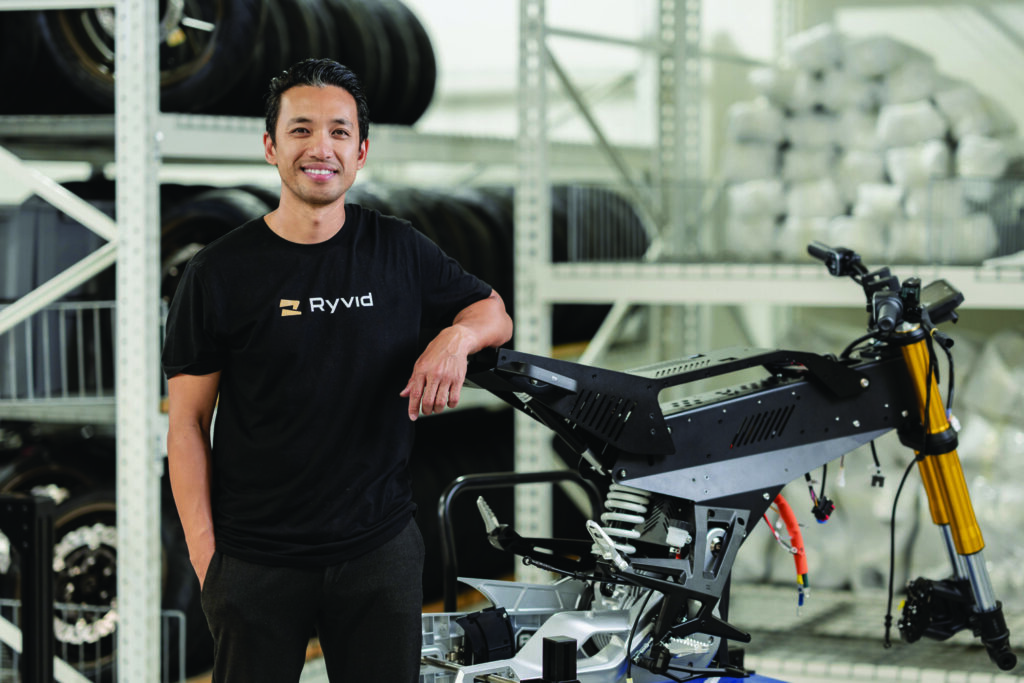

Founder and CEO Dong Tran explains: “In Vietnam, motorbikes are the only way to get around and there’s no age limit to ride, so as a kid I rode a lot of scooters. When we were starting the company, we were looking at transportation as a whole and thinking what can we, as a company, create that can make the biggest difference 10 years down the line.

“Is it a car? Is it a UTV? A power sports vehicle or a small little moped? And we landed on the fact that in 10 years, the majority of the world will probably still be on a smaller-type moped, a small vehicle, and making that type of vehicle as an EV made a lot more sense to us than creating a big truck or SUV, just because of the power density.”

A new market of opportunity

The concept is simple. Tran says Ryvid’s bikes are “glorified scooters – and I say that lovingly” with “twist and go” capabilities. They are easy to ride, easy to manage, lightweight and have good range. They do require a license to ride, but Ryvid will cover the cost of that “because we want responsible riders and we want this to be a transportation tool, not just a toy.”

This, however, is a bike that could never have existed until recently. In the last 10 years, the supply chain base has become “a whole different place,” says Tran, because the explosion of China’s EV component supply has led to better, cheaper motors, more efficient batteries and a gamut of controller and software options.

Everything is now a proven commodity, and that is what gave Tran and his two fellow co-founders – who also hail from different areas in the automotive and aerospace design and engineering sector – the confidence to grow Ryvid from a conceptual idea in 2018 to shipping almost 1000 units in their first year of production last year.

“When Zero Motorcycles started in 2006, they didn’t have a bunch of controllers to pick out; they had to do their own motors, their own battery management system (BMS),” explains Tran. “Now, you can go to 10 different vendors and pick out a motor controller or a BMS, everything is pick and choose and that drove the price down tremendously.

“The self-build market, where people are buying these things and converting their own bikes, has matured to the point where these parts are proven; they’re used by hundreds of thousands of people, so they became a commodity. What you can control is the BMS, which ultimately is the modern-day engine, so that’s a really important thing on the bike.”

Just collecting a selection of components together to create a bike for the target market was not what Ryvid was about, however. Each of its founders had different passions and different areas of expertise, but all were aligned on one thing: to take a holistic approach to sustainability by creating an electric bike that was also easy to manufacture and maintain.

“The biggest aim was producibility, if that’s even a word,” offers Tran. “I’ve been in a lot of start-ups and companies that raise a lot of money, do amazing concepts, and they get to the point where they have to manufacture it and they fall flat on their face every time. It comes down to designing something that’s not producible and not easily put together.

“We wanted to avoid that mistake, particularly given we initially had to put these together in California, one of the most expensive places you can make things! We needed to reduce component costs and labour costs, and the aim was to design it so it could be made anywhere, with a labour force that is not even trained to put together motorcycles.

“As a result, we are very anti-complexity. Anything that puts a failure point onto the bike we wanted to get rid of. Water cooling was something that could fail, so we got rid of that. Even a transmission is a point of failure; you have to put oil in and it fails, so we sized the bike to the very specific use case so it doesn’t require that.

“It was completely optimised to a level that would be impossible with a petrol engine. It looks like a motorcycle and it has standard components – suspension, wheels, brakes – but everything about the frame and the chassis is different because we had pretty much free reign and we optimised it purely for handling and performance.”

The power to perform

The team worked with QS Motors to develop a custom air-cooled motor; a 72 V brushless DC unit, rated at IP67, which delivers 6500 rpm. That is coupled to a direct belt drive with a 4.7:1 ratio, giving a lot of torque but without a transmission and maxing out at 27 kW, which, Tran says, is “more power than you ever need” on this type of bike.

The motor also employs flux weakening at the top end, reducing torque at high speed by allowing the motor to rotate a little faster. Most modern electric motorcycles have some sort of system such as this to help with the top speed, and given the choice of direct drive, it was especially important on Ryvid’s machines.

The battery uses the same P58 cells that are found in Zero Motorcycles’ range. These are high-quality lithium-ion nickel manganese cobalt pop cells, which have very fast charging capabilities and a very high power-to-weight ratio. The unit’s total capacity of 4.3 kWh delivers 50–70 miles of range, which is the target distance for this type of bike.

One of the most innovative parts of the Ryvid drivetrain, however, is not what is in it, but how it is mounted. The size of a traditional petrol engine requires it to be fixed in position on the frame, with slack built in to compensate for belt or chain stretch from the relative movement of the wheel on the swing arm; not the case with this compact electric solution.

“We designed that out completely, because the motor is part of the swing arm,” reveals Tran. “It moves with the swing arm, so we’re able to stretch our belt to the exact specs and not have to compensate for the movement. That makes it basically zero maintenance on the belt–it’ll run for 60–70,000 miles before you need to replace it.”

This solution has also enabled the team to design out the squatting effect often experienced on a motorbike, which tends to shift the centre of gravity and affect handling and acceleration. Tran adds: “The anti-squat design effectively counteracts the force of the wheel and the bike stays completely level throughout acceleration.”

In innovation, copying is a form of flattery and, on that basis, Ryvid has clearly done things right because the new Can-Am Pulse and Origin bikes, which have recently been launched, follow the same route of having the motor built into the swing arm. No doubt, over time, other manufacturers will follow suit but, as Tran proudly claims, “Ryvid was first!”

The air-cooling solution is another innovation Ryvid has pioneered on its bikes, helped by Tran’s background in aviation. The team clocked up hours and hours of computational fluid dynamics work on aerodynamic solutions and the result is a precision-designed airflow regime, which aims to keep the battery and motor at optimum temperature for the bike’s full range.

“The design is enabled by the simple electric drivetrain because there is nothing to get in the way,” explains Tran. “We have custom fins that pop up in the direction of airflow. The battery has an inlet at the front, the air goes through the casing and out of small vents on the side, then it comes right through the side panel and tucks into the motor.

“The motor casing was designed with special cooling fins that are upright, and they catch the air. Essentially, we cool the battery, then cool the motor, and then it shoots out the back and does some pretty interesting aero effects. If we max out at full throttle the whole time, the motor will never overheat–and that was the simple design requirement.”

Controlling performance

One of the things the team looked at closely was how much technology and adaptability to put on the machine for the end user. The conclusion was to make a bike that performs well but is simple to use, and that led to the selection of two specific off-the-shelf controllers that make the bike’s operation as simple as possible.

The standard bike uses a Volta power controller, while the higher-performance model uses one from ASI, manufactured in Canada. The harness is designed to fit both units and they also both work with the same batteries, giving full flexibility for users to select the performance level they require from the start.

In time, the company plans to develop adaptable software and additional features, but that is simply a development of the firmware and software controlling the BMS management. One thing that was essential, however, given the operational temperatures in the target markets, was to develop programming that could manage ‘beyond-normal’ situations.

In most cases, air cooling is perfectly satisfactory, but in exceptional circumstances, the motor controller can kick in and help manage the system. “There’s a lot of safeties put in place to make sure that the motor and the BMS don’t overheat, and that the controller doesn’t blow itself up,” explains Tran.

“The aim was to get strong enough performance that it feels exciting to ride without overly stressing out the system. We created our own battery discharge table that controls our motor controller, so at different speeds, different performance, different temperatures, it varies the output of the battery.

“We had to do a lot of custom tables to make that work well and the end user doesn’t really notice. They just know that at a certain battery range it will slow down slightly because it needs to manage its output. Obviously, this can get a lot smarter and we have every plan of making it quite a bit smarter.

“We have sensors on the bike that know the lean angle, and that’s already all built into the harness. That, for us, is just developing the software that will get distributed later on and it can be downloadable for anyone, anywhere. There’ll be an app that comes out that works with the controller to make it increasingly intelligent.”

The controller is also programmed to enable the motor to run backwards, meaning that unlike any petrol bike, this machine actually has a reverse gear. “That’s a free feature that when we launched felt like a no-brainer,” says Tran. “People just didn’t do it on electric motorbikes before we did, but they do now!

“Initially, everyone thought it was a bit weird. Why would a bike need to go in reverse? Then they worked it out; when they’re parked on a slope and can’t push the bike out. People love it. You wouldn’t stick a reverse gear on a normal petrol bike because it just adds more complexity and weight, but for us, with electric, it is just a bit of software!”

The bike also employs an intelligent regenerative braking system which, although far less powerful than it would be on a car because of the reduced tyre surface area, is so effective that the pads that are used in the traditional braking system that sits alongside do not have to be changed for the entire life of the bike.

The system uses careful automatic software management to avoid the bike skidding out, particularly in the rain, and Tran says: “Technically, you could manage with just the regen brakes. We still fit standard brakes because of the regulations but, essentially, we never have to use the rear brake because the regen does most of the work.

“We have two modes. First, when you let off the throttle, it kicks on a small amount of regen to slow you down. You can feel it a little bit, but it’s not going to stop you. Then, we have a stronger regen as a trigger on the left-hand side. Instead of having a rear brake handle, like you typically would, you pull the trigger to do more regen and come to a stop.”

Removable battery design

The battery fitted to Ryvid bikes is designed to be fully removable. Constructed as a single unit, it can be unlocked, tilted down and pulled out at ground level without having to take the full weight of the battery and without having to use any tools at all. Putting it back in requires a simple tilt, after which it latches back into place.

According to Tran, these simple procedures can be performed in as little as 15 seconds, giving the bike complete hot-swap capabilities. However, with a full charge from zero taking as little as 90 minutes on a standard connection, and a second battery costing just shy of $4,000, it seems unlikely that most owners would bother buying a second unit just to save charging time.

Tran acknowledges that is the case – aside from a few of the company’s current fleet users such as the police, government agencies and riding schools – but it turns out that it is only one of the reasons the battery was designed in such a way. There are, in fact, two other far more interesting use cases for it.

“The ability to use the battery off the bike was something we really wanted to offer,” says Tran intriguingly. “It has wheels and a little handle that pops up, so you can actually roll it off the bike and use it as a portable power station, like a generator. You can take the battery and go camping or use it to power anything you want.

“In Vietnam, there’s a lot of brown-outs. They don’t have a solid electrical grid, so having some battery power is actually very beneficial. Also, because the battery is self-enclosed, with a

3.3 kW onboard charger, you can plug it in anywhere; in fact, you can even roll into a Starbucks and plug it in there for free! It’s amazing!”

The other benefits of the removable battery are serviceability and manufacturing complexity, and Tran continues: “The battery is often one of the biggest issues on electric motorbikes, but also one of the biggest potentials for upgrade. Yet, for a standard manufacturer, battery replacement takes months because they have to take the whole bike apart to get it out.

“We anticipated that. So, with the removable battery, replacing it is as simple as shipping it back to us. We ship out a new battery in a crate, the owner pops it on basically the same day they get it, they put the old battery back into the crate and they ship it back to us. We’ve already done that with some of the bikes that are out there and it’s such a simple process.”

Finally, because the Ryvid range is interchangeable, the same battery can be used for other bikes. So, in the same way that a power tool manufacturer builds loyalty by selling other tools in their range without the battery, if someone buys one bike, they can buy another without the battery and swap the battery between them, cutting out one of the major costs.

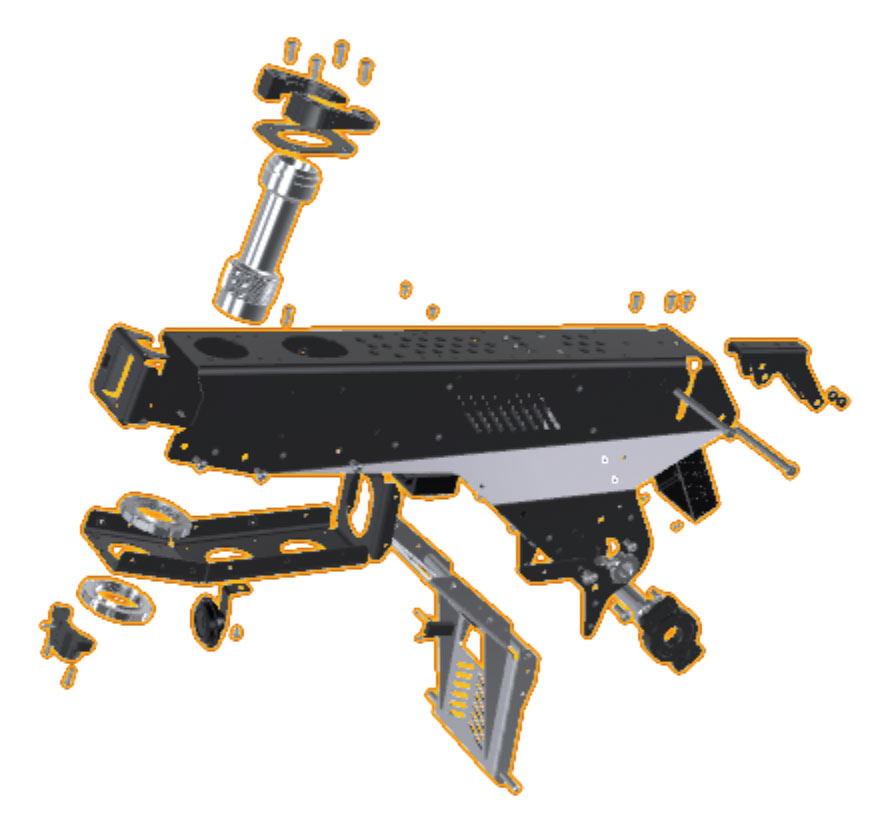

Innovation in frame design

The frame design was driven by the team’s desire for simplicity, and the innovation here came from Tran’s aviation experience but also from his work with a rather offbeat company that created unusual 3D paper model sculptures, designed in CAD and hand-made from a single pre-folded, pre-creased sheet of paper.

Instead of following the welded frame approach seen in most traditional motorcycles, Ryvid explored the potential to manufacture from a folded sheet of metal, as Tran explains: “When we designed the airplane, nothing was welded, everything was bonded, faceted and riveted. That was beneficial for weight and strength and it also kept the costs down.

“Glue has become really good now, and riveting technology is much more accurate, so we leveraged both of those on the motorcycle. It seemed straightforward but, in hindsight, the process was anything but! To mount our entire front end, for example, we had to figure out how to attach it without welding it and make sure it could last 100,000 miles.

“We went through many, many iterations, but what we ended up with was essentially a frame made from a flat sheet that is laser cut and folded with a CNC press. That makes it extremely strong, because it’s a box structure, but it can be iterated very quickly, it can be made out of any material and it can be made anywhere.

“We tried it out of aluminium, stainless steel 316 and stainless steel 306. We could do it out of titanium if we really wanted to! We ended up choosing 360 stainless, mainly because it is the most corrosion resistant. But the game changer is that we can put a frame together in about 20 minutes with a rivet gun, some fasteners and no specialist skills.”

The suspension components are fairly similar to any petrol bike of this type, although the fact that the electric bike is slightly lighter means the set-up can be slightly softer and offer a more comfortable ride, with some additional tuning work on the front internals to provide a real motorcycle feel, and adjustment to the rear spring rate to account for anti-squat.

The seat, which is also easily attachable, is no ordinary bike seat. It is a movable design that is electrically actuated, giving the rider the ability to adjust their position for maximum comfort. What might look like a sales gimmick, however, actually turns out to be one of the functions that is most popular with Ryvid owners.

“It was inspired from mountain bikes,” says Tran. “If you look at downhill bikes, they have a seat that raises and lowers as you need it to. Initially, it was supposed to be a manual system but then we put an electric actuator on there because it’s easier. At first, people think it’s not going to do much, but then they get on it and they love it.

“Again, it’s all made possible because of the electric drivetrain,” and Tran continues: “There’s no engine or gas tank in the way, so that makes it very simple, and having a seat that can adjust to your height goes a long way. It’s been great for new riders, because they get on, they’re really uncomfortable at that height, so being able to lower the seat was a big deal.

“You can even change it while you’re moving, and although it’s not dynamic, so it doesn’t adjust based on speed, that is something we have coming down the line. It just needs a software update and, ultimately, we want to get it to a point where if you come to a stop, it just lowers so you can be more comfortable at the red light.”

Balanced for performance

The bike had many evolutions before it reached customers, including an early-stage plan to manufacture the frame out of aluminium. That actually made the entire bike 25% lighter, but stainless steel proved to be a more optimal solution. So, the design process was focused on maximising strength but minimising weight in every area possible.

The team carried out a rigorous testing programme, with bench testing for the drivetrain components; around 3000 miles of road trials, mostly to test suspension components; and 50,000 miles on a shaker table to ensure the durability of the weld-free manufacturing approach, which was an unknown quantity that did not exist in the market at the time.

A significant amount of structural simulation and testing was also performed on the battery mounting, which places the full 39 kg of weight on the swing arm. It was vital to ensure the fixing had built-in redundancy, to prevent it from flying off the bike in an accident, and Tran attests: “We’ve had a few crashes from our customers, and that has never been an issue.”

The combination of a lightweight battery and frame results in a bike that weighs 142 kg in total, with the battery taking up just over a quarter of that at 39 kg. That is low when compared to a bike like the Zero, which has a battery weighing in at around 90 kg and must be fixed owing to such high weight.

While minimising battery weight was important to make the removable solution possible, it was equally important for Tran to ensure that any weight on the bike was positioned correctly. Thus, the entire layout of the bike was based on getting the weight in exactly the right place to deliver a comfortable, smooth and reliable ride.

“As a motorcycle guy, weight distribution was really important to me,” explains Tran. “A lot of electric motorcycles out there are basically two wheels with a motor and a battery. Many manufacturers don’t really look at them as motorcycles – they just put a motor on and they go, but very often their ride and handling end up being really poor.

“Just because a bike is electric doesn’t mean it has to have crappy ride and handling. The majority of our weight is on the lower half of the bike, which makes it very manoeuvrable. We’re one of the very few bikes that have perfect 50–50 distribution. We did that through the motor and battery placement, and it allows the person to do the shifting, not the bike.”

All this results in a machine with exceptional performance. Tran says it can “pretty much beat any bike off the line” and can reach 30 mph in an eye-wateringly rapid 1.2 seconds. After that, the performance tails off a little, taking around five seconds to reach 60 mph and reaching a top speed of 84 mph. But it can also be tamed for more rookie riders.

“I think performance for this bike is more than it needs to be overall,” smiles Tran. “We’ve had people who ride 600s hop on our bike and think it’s way faster because the feeling of not shifting, the continuous power. It’s very smooth, but it can also be toned down with the Eco mode, which is about half that performance, to make it more manageable.”

Adaptability for all

Ryvid has cleverly developed a three-bikes-in-one solution to reach as many customers as possible. The Anthem is designed to be the city commuter, the Outset has a more rugged demeanour and is marketed as a bike for adventure in urban areas and beyond, while the third, currently codenamed the Mini, is coming soon.

The main chassis, frame, motor and battery are all the same across the range, and the only differences are in the suspension, seat, headlights and handlebars. The entry-level Mini, which will be similar to a Honda Grom, is “aesthetically very different” but still built off the same chassis, just with 15 inch wheels, smaller suspension, different seats and a lower price.

“Our three models share 80% of their components,” explains Tran. “That allows us to scale really quickly with the supply chain and everything is interchangeable. So, a customer can buy Anthem headlights and put them on the Outset and vice versa. The same with the seat and side panels, and we even offer detachable coloured panels for a quick colour change.

“Accessories are a really important aspect of this type of bike, so we also have built-in inserts for M6 fasteners all over the bike, so you can attach anything to the frame, and we have already developed a lot of aftermarket parts for that. These bikes are extremely versatile and we don’t play this up enough, but you can really customise them to your liking.”

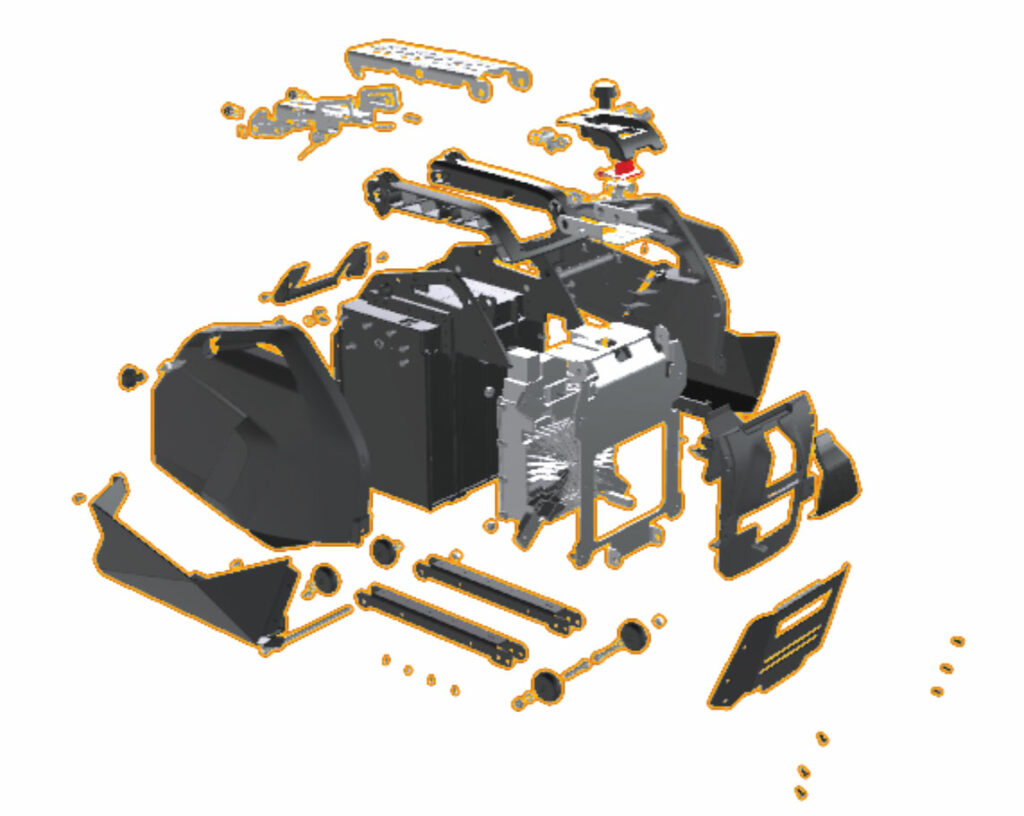

When it comes to manufacturing, the bikes have been split down into five sub-assemblies – the swing arm and integrated motor, the frame, the front end, the seat, and the rest – and an entire unit can be put together, from scratch, by a single person in around an hour and a half. Do that with five people in parallel, and suddenly hand-made volumes rapidly rise.

That time-efficient manufacturing approach is, of course, ideal for the market the team is targeting. The low labour costs in the Far East should make it possible to construct the bike over there far more cost effectively than is achievable on the current line in California, and with a full factory of manual workers, the stage is set for rapid roll-out.

Tran believes that, for now at least, Ryvid has opened up a niche market when it comes to electric motorcycles, and he explains: “This is an extremely competitive industry but it’s currently split into two distinct spectrums: electrified pedal bikes and dirt bikes, and big powerful bikes, with not much in between.

“Electrified pedal bikes, like the Super73s and Rad Power bikes, are very popular and sell a lot, while electric dirt bikes – your Surrons, Eride Pros, Tallarias – are what this super-young generation are growing up riding. These bikes live in a grey space. I consider them to be e-motorcycles, but they see them as e-bikes because you don’t have to license them.

“In the US, they’re starting to crack down on them now, and we saw this coming a while ago when we started the company. Eventually, kids will get into trouble and do things they shouldn’t and that’s starting to happen. So, these bikes are starting to be looked at in terms of new legislations.

“On the other end of the scale, the really big powerful bikes – the LiveWires, Damons, Zero Motorcycles – are well suited for the American market in terms of size and speed, but some of the players in that space are starting to think about smaller motorbikes, for example, the BMW CEO2 and CEO4 and the LiveWire S2 Del Mar.

“I think people are starting to realise, especially with the bigger bikes, you’re not getting the value proposition. They tend to be a lot more expensive – around $15,000 to $20,000 – but because of the power they produce and the drag factor they create, the battery can’t go that far and their range, although better than we get, is not three times better.”

Growing into the future

This is an exciting time for Ryvid and, after putting 1000 units into the US market, the company is about to realise the next part of its plan and take the bikes to Asia. “The existing bikes we have are going to go into the India and China market as is, and we don’t need much of a market share for that to be successful,” Tran explains.

“The Mini will then go to Indonesia, the Philippines and eventually Vietnam. We chose Indonesia first, mainly because it’s one of the fastest-growing markets for two-wheeled electric vehicles. They already like the bigger bikes over there, so we’re going to try out a few markets and see which one makes the most sense.”

Things do not stop there, however, and it turns out that the plan extends beyond two wheels. Tran continues: “Motorcycles are an important part of the company’s DNA, but that’s not what the company’s aiming for. If you go to Asia, you see these three-wheeled, smaller tuk-tuk type vehicles, and there’s a reason why they’re everywhere.

“These are very useful vehicles and they use the motorcycle drivetrain. So, while we believe there is huge potential for our two-wheel range, that will end at the three products we have now and, ultimately, our next product won’t be two wheels, it will be an electric entry into the massive three-wheeler market.”

Tran believes that the core to Ryvid’s success is its focus on a small battery unit, which will also follow into new designs. The Far East runs on 220 V as standard, meaning rapid charge speeds are easily achievable everywhere, and although the grids can be unstable, the rapid growth of localised solar power should eliminate much of that concern.

“I don’t think the infrastructure, in terms of charging, is going to hold us back,” he concludes. “That is honestly the reason we did a small battery. It’s not ideal for the United States right now, although it’s really good for urban areas, but it’s going to be really perfect for the cities in the up-and-coming countries we are going to – and, in fact, for all cities in the future.”

It all comes back to the ultimate aim of reducing emissions in the heart of the world’s cities. In the long term, Tran sees these bikes as being not just for the Far East but for everywhere on the planet: “It’s not that we just launched in the US blindly,” he concludes. “The reason the Far East cities use bikes is the same reason why we need them here.

“What they’re doing over there is 100 percent what we need to be doing everywhere. If you go to LA or New York in traffic hours, you can’t get around because there’s too many people. I think the younger generation gets it. I see more kids on e-bikes than anything else; they don’t want to drive cars anymore. We just have to convince enough people of that.”

Meet the founders

The three Vietnam-born US-based engineers and one US-based investor who formed the founding team at Ryvid have a wide range of diverse and interesting backgrounds, as CEO Dong Tran explains: “I’m an automotive-turned-aerospace designer with an engineering background. I worked with Honda, General Motors, BMW Design Works and in Toyota’s small micro-mobility department in Tokyo, then did a stint at Icon Aircraft, an aerospace start-up which had turned into a fairly large company of almost a thousand people by the time I left.

“After that, I started my own company working on product development, from design all the way through engineering, prototyping and production design. We worked for a lot of different companies, including some electric mobility companies including Zero Motorcycles, Polaris, and that’s where the idea for Ryvid popped up.

“The other founders were in similar fields. One was in the aerospace supply chain, another a mechanical engineer designing a lot of the tools and equipment that make semiconductors, and the fourth, our investor, has a military background. He was a Commander on the US Virginia Class submarines. So, we are a pretty interesting group of guys!

“I’m the only ‘bike nut’ hardcore motorcyclist and after riding scooters in Vietnam, I came to the US and got a 750 GSXR! I just thought it was the biggest bike you can get! So, first I went big, but then I went really small, I went into dirt bikes, then the Honda Guam when that first came out and then mopeds, so I really got back to the roots of small bikes.

“Everyone had their own passion, but right from the start we were all aligned on one thing, which was sustainability—not in the sense that it’s just simply electric, but we were really interested in sustainability as a holistic approach. How do we design and manufacture the whole product so that it is sustainable? And that is what drove the entire design.”

Specifications

Ryvid currently produces two different bikes—the Anthem and the Outset—but both are based upon the same platform and follow the same specifications and performance.

Top Speed: 84 mph

Range: Urban/Highway/Combined – 75/46/57 miles

Wheelbase: 1321 mm

Weight: 142 kg (103 kg bike/39 kg battery)

Rated Power: 10 bhp/7.5 kW – equivalent to a 250 cc bike

Peak Power: 18–20 bhp/13.5–14 kW – equivalent to a 500 cc bike

Motor: 72 V air-cooled brushless DC, IP 67, 6500 rpm with flux weakening

Motor controller: 72 V, 92% efficiency, 250 A peak, 3-phase brushless controller with programmable regenerative deceleration

Drivetrain: Rear drive unit, integrated into the aluminium die-cast swing arm, integrated cooling fins on motor and integrated belt dust cover

Transmission: Clutchless direct drive, Continental Synchroforce Carbon Belt, 4.7:1 ratio

Battery: 4.3 kWh 72 V (nominal) lithium-ion battery, 85 V when fully charged

Charging: 3.3 kW charger integrated into the battery pack – 80% charge in 1.25 hours with 220 V 40 A; 2.5 hrs with 110 V 16 A

Click here to read the latest issue of E-Mobility Engineering.

ONLINE PARTNERS